by S. Dorman

Going home through Franconia Notch, my spouse and I watched the great Whites rising like an apparition glimpsed between darker mountainous slopes. This whiteness—befitting the name of the range—was rime ice, crusting bold surfaces, before disappearing a day or two later. Then we searched for the telltale contour of Agiocochook, as Native Abenakis fitly named the greatest for its vast white summit: The Snowy Forehead

Of these Presidentials Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, “Let us forget the other names of American statesmen that have been stamped upon these hills, but still call the loftiest Washington. Mountains are Earth’s undecaying monuments.”

Hawthorne’s stories in The Old Stone Face and Other Tales of the White Mountains are, as you might expect, homey, austere, and slightly fantastic. I find the obvious word in it all is “stone.” The word is here by the dozens and the word “rock” also features—less so, maybe a dozen times.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was college-mates with Longfellow at Maine’s ivy league Bowdoin in the early 1800s. The great poet ended up reviewing Hawthorne’s first book, Twice-Told Tales, which contained a couple of the stories in this later White Mountains book. In his review, Longfellow said, “A calm, thoughtful face seems to be looking at you from every page, with now a pleasant smile, now a shade of sadness, stealing over its features. Sometimes, though not often, it glares wildly at you with a strange and painful expression.”

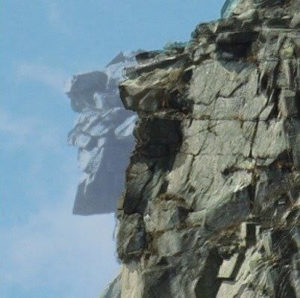

“The Old Stone Face” story (1850) assumes the lastingness of stone formations. Based on “The old man in the mountain” of Franconia Notch, this stone-sculpture of God the Creator figures in his tale. In this title story he writes:

True it is, that if the spectator approached too near, he lost the outline of the gigantic visage, and could discern only a heap of ponderous and gigantic rocks, piled in chaotic ruin one upon another. Retracing his steps, however, the wondrous features would again be seen…. Like a human face, with all its original divinity intact … until, as it grew dim in the distance, with the clouds and glorified vapor of the mountains clustering about it, the Great Stone Face seemed positively to be alive.

In “The Great Carbuncle,” the stone is something of a rosy guiding light, glowing among mountain mists but seldom stationary—elusive. In the non-fiction “Sketches from Memory” the author’s own search for stories and experiences leads him through the real world stone walls of “the notch.” He seeks through travels in the Crystal Hills to find his own metaphoric experience of the tempting red stone.

In “The Great Carbuncle,” the stone is something of a rosy guiding light, glowing among mountain mists but seldom stationary—elusive. In the non-fiction “Sketches from Memory” the author’s own search for stories and experiences leads him through the real world stone walls of “the notch.” He seeks through travels in the Crystal Hills to find his own metaphoric experience of the tempting red stone.

His style is crystalline as well. For one thing, it’s slow. In this figure, it’s like the slow calculated building of atomically precise structuring found in White Mountain gemstone: amethyst, beryl, tourmaline, or quartz. These building forces are subterranean, seeming cold and crushing, but in fact are molten, incalculably hot and driven by energetic fusion only mineral elements can endure in order to bring forth lasting and mathematically precise light-enhancing beauty. The style can seem cold, ironic, stylized, but in its light-capturing array we glimpse unbreakable morality, stern and unyielding as Hawthorne’s puritanical spirit—without the Puritan sect’s letter, some of its misbegotten laws, and its code of enforcement.

From Hawthorne’s perspective, this eternal unbreakable spirit works in this life—no matter the culture or era—as we are forged by fate into whatever we are meant to be; in collaboration of our free will with physics—the physical laws by which both we and the world are made. In Hawthorne’s vision, this fate is coupled with doom or the judgment of this invisible moral logos, or Word.

Edgar Allan Poe had good things to say about Hawthorne’s early artistry in the May 1842 Graham’s Magazine. Poe was grateful to him for helping establish American letters, specifically the short story, saying Hawthorne’s belonged to “the highest region of art… art subservient to genius of a very lofty order.” In this article he viewed the stories of Twice-Told Tales as foundational, and gave an example of what he called Hawthorne’s peculiar ability:

Mr. Hawthorne is original at all points. …Not all is done that should be done, but there is nothing done which should not be. Every word tells, and there is not a word which does not tell…. A tone of melancholy and mysticism [prevails]. The style is purity itself. Force abounds. High imagination gleams from every page.

We don’t want to think we can break a moral law, or that a moral law can break us. In Hawthorne the moral law is inset in the Creation like gravity, which brought down the stones when erosional forces loosened them. We—the humans—are that portion of creation dedicated to morality’s encoded expression. As all physicality expresses invisible gravity, so humanity experiences invisible moral law. Throughout Nathaniel Hawthorne’s work we find morality both mocking and aiding humanity.

Where gravity is impersonal, the hopeful Crawford Notch householder character nevertheless gives personification to the mountain. So in Hawthorne’s work morality is also personal, not impersonal. In Hawthorne’s we are persons, as is God.

Hawthorne’s “Crystal Hills” were exposed in a massive erosional off-scouring of glaciers. Erosion continues, and on our day trip, we saw its testament in topographic changes to the surface of the Franconia Notch profile. He wrote of this real-life stone surface—the basis of the first story—as a ruined chaotic pile. But even at that time, it was still intact as “the old man in the mountain.”

The first time I saw the great granite face it was braced with iron but still very much recognizable—high above—as the iconic natural emblem of New Hampshire. One might even say of New England. I heard of its fall over a decade ago, and recently we came through the Notch to see its remains high on the once-anchoring cliff-face.

In “The Ambitious Guest,” the narrator’s host and head of the house wishes they could move, even though he says of the mountain, “We are old neighbors and agree together pretty well, upon the whole. Besides, we have a sure place of refuge hard by if he should be coming in good earnest.” Hawthorne has scattered the odd rattling, rolling, falling stone throughout this masterful story so that their sounding reaches the reader’s ear (along with that of the householders’), heightening the overall force—much as Poe said about the reader’s ear in “The Hollow of Three Hills,” another Hawthorne tale. “Mr. Hawthorne has wonderfully heightened his effect by making the ear, in place of the eye, the medium by which the fantasy is conveyed.”

However, based as it is on a true story of what happened in the Crawford Notch, the house stands. The people who hoped for kindness, but also feared their mountainous neighbor, fled when they might have stayed alive in the house. Shielded by a ledge, their dwelling afterward stood between the arms of the landslide that destroyed them. My retelling clumsily echoes all the hard and fearsome parts of both Hawthorne’s story and the puritanical scripture on which (among other literary masterpieces) he was raised.

Hawthorne’s “Sketches from Memory” is the last of this small collection. In this, his depicted travels-through-the-notch experiences, receiving glimpses of things to come in the making of these stories. “The notch” itself intrigues him. He tries and feels he has failed to describe its effect on him:

It is, indeed, a wondrous path. A demon, it might be fancied, or one of the Titans, was travelling up the valley […..] Shame on me that I have attempted to describe it by so mean an image—feeling, as I do, that it is one of those symbolic scenes which lead the mind to the sentiment … of Omnipotence.

Instead of conflating fictional characters out of real fellow travelers suggestive of his themes, he divides surface attributes of these individuals into separate types, to allegorize fictive seekers after the carbuncle. But we might also surmise, given his early felt discouragement over prospects of publication, that he plays gently off himself as the ambitious guest who is destroyed with his hosts in the Titan’s “elbowing of the heights aside” in Its monstrous passing.

We today can surely marvel at what Hawthorne has to say in parodying his own tastes in literature. Especially if we cannot detect its satire, or know little of historical shifts in culture, or lack a sense of complexity in coupling these shifts with our own unchanging human nature.

To be easy about Hawthorne’s uses, we think our own old stone face should object. But if, however, we think of the Native Americans selling the businessman for ransom in “The Great Carbuncle,” and then perhaps recall what the Titan Time did to the real-life historical “Old Man of the Mountain,” we might think of our unchanging nature.

In Hawthorne’s artistry, we now have the legend of the great carbuncle out of Native American lore. Being true to his own tastes, he nevertheless gives artistry its due, maybe wildly, glaring in times and places: from the ancient and classical, through the primal native lore—in allegory and archetype—even to his own day.

© S. Dorman

- Dorman has lived in Maine and studied its ways for thirty-five years. Maine in Winter is forthcoming this winter, forth book in the series of MaineMetaphornarrative nonfiction—put out by Wipf & Stock.

Visit the S. Dorman Author’s Page