Review: An Overall Look at Harry Potter

Article by Christopher G. Nuttall

One of the problems with being a writer is that you tend to look at a piece of someone else’s writing with a critical eye. Indeed, while I have enjoyed many books since I became a writer myself, I have also found myself thinking about how I would have done it, if I had been writing the book. (And, when I have encountered a book so perfect that I couldn’t muster any criticism, I have been lost in admiration for the author.) That is not to say that I didn’t enjoy the books. I have deeply enjoyed reading most of Harry Potter. But, at the same time, there are both good and bad aspects of the series that should be highlighted.

There is very little that is truly original in Harry Potter. Rowling drew on boarding school tropes that were established long before Rowling was born and, I suspect, magic school tropes that owe a great deal to The Worst Witch and – going a long way back – The Wall Around the World. And yet, Rowling breathed new life into these tired old tropes. She created a world of magic and mystery, a world that kids could love and enjoy and learn some vitally important lessons from. It is impossible to praise her enough for getting kids reading again! She deserves every last bit of her success.

There is very little that is truly original in Harry Potter. Rowling drew on boarding school tropes that were established long before Rowling was born and, I suspect, magic school tropes that owe a great deal to The Worst Witch and – going a long way back – The Wall Around the World. And yet, Rowling breathed new life into these tired old tropes. She created a world of magic and mystery, a world that kids could love and enjoy and learn some vitally important lessons from. It is impossible to praise her enough for getting kids reading again! She deserves every last bit of her success.

But, at the same time, it is important to acknowledge Harry Potter’s limitations. The series tried to grow up with its main character. The zany aspects of Philosopher’s Stone and Chamber of Secrets, with their comic relief that might well have drawn on Roald Dahl, gave way to the growing darkness and ambiguity of Prisoner onwards. This created the problem that the later volumes were not suitable for children, while adults looked back at the earlier volumes and shuddered at the unfortunate implications. An adult can admire a book written specifically for children, even as he notes the plot holes; it’s harder to overlook such issues in a book written for older teens or adults. Harry Potter’s structure makes it impossible to discard chunks of the series that were aimed at children, yet it also makes it impossible to overlook the implications. I respect Rowling hugely for what she tried to do, but I feel she didn’t quite pull it off.

On the minor scale, there’s the treatment of the Dursleys. In the first books, they are nothing more than comic relief. They have a great deal in common with Matilda’s (Roald Dahl) parents and brother. But, in the later books, it becomes clear that they have been victimised – by Dumbledore. They are, at best, conscripts in a war they can neither fight nor escape. Indeed, the whole idea of literally leaving Harry on their doorstop for them to find in the morning is thoroughly absurd. How would the Dursleys account for his presence in their home? Does he even have a legal existence in the muggle world? And how do they pay for his expenses? They can reuse Dudley’s baby clothes – to put this in some context, the clothes we bought for my son when he was a baby have served two other babies with no problems – as Dudley was presumably bigger than Harry – but other things would have to be brought new. Harry would need a car seat, a pushchair (a double pushchair would be expensive, particularly as they would have already invested in a single-seat for Dudley) and quite a few other things. And all of this would be a major expense when – I suspect – the Dursleys are already facing serious financial difficulties. It’s hard to blame them for resenting Harry’s presence in their house.

On the minor scale, there’s the treatment of the Dursleys. In the first books, they are nothing more than comic relief. They have a great deal in common with Matilda’s (Roald Dahl) parents and brother. But, in the later books, it becomes clear that they have been victimised – by Dumbledore. They are, at best, conscripts in a war they can neither fight nor escape. Indeed, the whole idea of literally leaving Harry on their doorstop for them to find in the morning is thoroughly absurd. How would the Dursleys account for his presence in their home? Does he even have a legal existence in the muggle world? And how do they pay for his expenses? They can reuse Dudley’s baby clothes – to put this in some context, the clothes we bought for my son when he was a baby have served two other babies with no problems – as Dudley was presumably bigger than Harry – but other things would have to be brought new. Harry would need a car seat, a pushchair (a double pushchair would be expensive, particularly as they would have already invested in a single-seat for Dudley) and quite a few other things. And all of this would be a major expense when – I suspect – the Dursleys are already facing serious financial difficulties. It’s hard to blame them for resenting Harry’s presence in their house.

None of this, of course, excuses their treatment of Harry. The Dursleys are not, by and large, physically abusive (they are certainly not the monsters beloved of stories where Harry is rescued by Snape/Dumbledore/Voldemort/etc), but they are emotionally abusive. They do not show Harry even a fraction of the love and affection they shower on their own son (which may be a reflection of Petunia’s awareness that, one day, Harry will enter a world that Dudley will never be able to join) although, given that Dudley is a spoilt brat and a bully, this is not a bad thing. Harry may not have been loved, growing up in that house, but he learnt that there was love. Tom Riddle did not have that education when he was a child.

Nor does this excuse the Wizarding World’s treatment of them. Hagrid attacks Dudley for Vernon snapping at him – Hagrid is never punished, as far as we can tell. A House Elf intrudes on their business dinner – again, they are never compensated for it. Fred and George nearly kill Dudley, a Dementor nearly kills Dudley (and Harry) … Dumbledore’s sanctimonious little speech in Half-Blood Prince is bloody cheeky when he is responsible for most of their problems. The Wizarding World has a huge moral blindspot when it comes to the treatment of muggles. Harry doesn’t even seem to recognise it.

Indeed, while the overall moral of the series is a strong one, there are many weak points – and moral blindspots – that have not gone unnoticed. Harry follows Dumbledore blindly, even though Dumbledore is setting him up as a human sacrifice; the Wizarding World has no qualms about love potions, even though they’re effectively date rape drugs; bullies like Fred and George are treated as heroes, just because they’re on the right side (this could also be said of James Potter and his friends); a quarter of Hogwarts (Slytherin House) is considered irredeemably evil … and Rowling rarely acknowledges any of this. Indeed, Dumbledore – given plenty of time to work against Lord Voldemort, prefers to sit on his hands and wait for Harry to grow up. Did Rowling trust us to draw our own conclusions? Or was she too wrapped up in childish tropes to focus on more adult points of view?

Indeed, while the overall moral of the series is a strong one, there are many weak points – and moral blindspots – that have not gone unnoticed. Harry follows Dumbledore blindly, even though Dumbledore is setting him up as a human sacrifice; the Wizarding World has no qualms about love potions, even though they’re effectively date rape drugs; bullies like Fred and George are treated as heroes, just because they’re on the right side (this could also be said of James Potter and his friends); a quarter of Hogwarts (Slytherin House) is considered irredeemably evil … and Rowling rarely acknowledges any of this. Indeed, Dumbledore – given plenty of time to work against Lord Voldemort, prefers to sit on his hands and wait for Harry to grow up. Did Rowling trust us to draw our own conclusions? Or was she too wrapped up in childish tropes to focus on more adult points of view?

The world Rowling designed is, at least at first glimpse, a child’s paradise. Magic and mystery, wonders and enchantments … owls flying through the sky carrying mail, a magical railway taking one to a magic school … what’s not to like? Rowling sucks us into her world effortlessly. But, as we grow older, we start to see the flaws. The Wizarding World has no sense of justice and it can be astonishingly cruel, from minor matters like letting Snape (and a whole string of other dodgy characters) teach children to far more serious issues like rampant discrimination against squibs and werewolves. Rowling set out to teach us that even a fantastic world like hers is not free of injustice. In many ways, she succeeded admirably.

Hogwarts itself is far from perfect. The ‘safest place in the Wizarding World’ is nothing of the sort. Like many real-life schools, including the one I attended, bullies run amok and danger lurks around every corner. (Rowling also depicts Boarding School Syndrome very well, as both Snape and Lupin regress to childhood when confronting each other.) When the teachers do intervene, they can be quite cruel. Dumbledore is painted as astonishingly progressive for abolishing corporal punishment, but – looking at the punishments Hogwarts does use – it seems as if it was little more than a piece of virtue signalling than anything real. Hogwarts has more in common with the darker schools of boarding school literature, I suspect, than many of the younger readers realised. Magic aside, Rowling got a lot right.

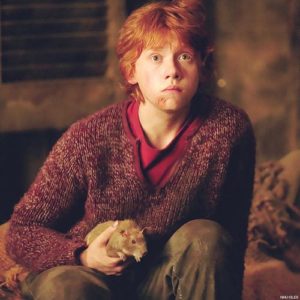

Rowling both matured and regressed when it came to character development. Looking at the three main characters, it becomes clear that the only one who had a dedicated – or at least successful – character arc was Ron Weasley. (Neville had an arc too, but he was a minor character.) Ron starts out as an insecure and hot-headed boy – overshadowed by his brothers, neglected by his mother – with a hunger for fame and fortune that is entirely understandable. (Ron keeps going over his successes again and again, I think, because he doesn’t really believe they are real.) It’s quite reasonably for him to envy Harry’s seemingly limitless supply of wealth and fame. He grows up, with a number of bumps along the way, into a reasonably mature young man.

Rowling both matured and regressed when it came to character development. Looking at the three main characters, it becomes clear that the only one who had a dedicated – or at least successful – character arc was Ron Weasley. (Neville had an arc too, but he was a minor character.) Ron starts out as an insecure and hot-headed boy – overshadowed by his brothers, neglected by his mother – with a hunger for fame and fortune that is entirely understandable. (Ron keeps going over his successes again and again, I think, because he doesn’t really believe they are real.) It’s quite reasonably for him to envy Harry’s seemingly limitless supply of wealth and fame. He grows up, with a number of bumps along the way, into a reasonably mature young man.

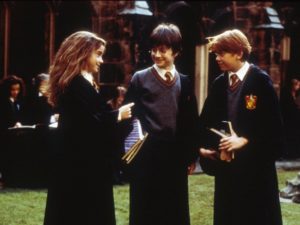

Both Harry and Hermione, by contrast, suffer from stunted character development. Harry grows up a little, but he never frees himself from a tendency to follow Dumbledore without question or to fail to look below the surface. This may well have been demanded by the plot – a smarter Harry would have realised, earlier, that Dumbledore wasn’t acting in his best interests – but it is more than a little frustrating if one likes one’s heroes actually thinking ahead. And yet, Harry has all the right qualities to be a hero. He is personally brave, committed to his friends and, when he realises the truth, steps up to sacrifice himself.

Hermione, by contrast, grows into a girl with more than a hint of utter ruthlessness, as well as a degree of naked sadism. Indeed, it is greatly to Rowling’s credit that Hermione’s negative traits do not go away after she befriends Harry and Ron. She is a borderline bully right from the start, accounting for her isolation; she thinks she knows better than anyone else, but she doesn’t learn (at least, within canon) that having the facts on one’s side is not the only thing you need to present your case. As I noted earlier, Rowling shied away from having Hermione take a pratfall in Half-Blood Prince, even though – by that point – Hermione desperately needs a learning experience. Hermione is the only character in the books that I liked less and less as the series developed. But then, of the main characters, she’s probably the least complex.

I don’t expect unflawed heroes and heroines. That would be foolish. But I find it hard to like a hero who is presented to me as an asshole, rather than the text directly or indirectly acknowledging their flaws. The only thing Rowling gives us along those lines is Hermione’s own self-dismissal as ‘books and cleverness,’ which is half-right. Hermione is simply not as clever as she thinks she is and it is only by the grace of the author that she doesn’t wind up with egg on her face – or dead.

I don’t expect unflawed heroes and heroines. That would be foolish. But I find it hard to like a hero who is presented to me as an asshole, rather than the text directly or indirectly acknowledging their flaws. The only thing Rowling gives us along those lines is Hermione’s own self-dismissal as ‘books and cleverness,’ which is half-right. Hermione is simply not as clever as she thinks she is and it is only by the grace of the author that she doesn’t wind up with egg on her face – or dead.

But this, too, may be an artefact of Harry Potter forever being trapped between a child’s series and an adult’s series. In a child’s book, you can turn your enemy into a frog and throw her out the window; in a adult’s book, that is the action of a sociopath and needs to be acknowledged as such.

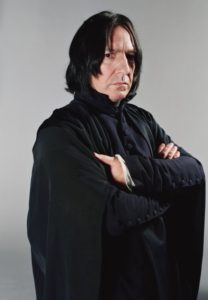

Rowling generally does better with the adult characters, drawing a collection of individuals who – the main adults in particular – are often deeper than they seem. Snape, of course, is the poster child for still waters running deep: presented to us as a strict, hopelessly biased (and borderline sadist) teacher, he saves Harry’s life on several occasions, plays a major role in the war and eventually gives his life to bring down Lord Voldemort. Others – Lupin, in particular – are never quite as they’re presented. It’s interesting to compare Snape and Lupin, simply because it’s clear that neither of them is anything like the surface personas they show the world. Snape risks everything to save the school; Lupin keeps a secret that could easily have gotten Harry (and everyone else) killed. Lupin is the nicer one; Snape is the better one.

Indeed, a great deal of misogynistic and misandrist nonsense has been written about Snape’s doomed friendship with Lily Evans, Harry’s mother. Once best friends, they had a nasty falling out that destroyed their friendship forever. Some commenters have blamed everything on Lily, some on Snape … sadly, and I give Rowling credit for showing this, the fault is a little harder to place. I suspect that what happened was that Lily clung to Snape, when they became friends before Hogwarts, because Snape was the only other wizard in the area; later, when they went to school, she made other friends … and Snape was suddenly a little embarrassing. The fact they were in different houses didn’t make things any easier. And then Snape, humiliated, lashed out at her. I can understand him, I can understand her … and I feel sorry for both of them. The boarding school environment is not conductive to mature reflection.

But then, neither Snape nor Lily – nor anyone – were completely good or bad. I had the impression, at least at first, that James had grown up a great deal after the Werewolf Incident, which was nothing more than a cold-blooded attempt, by Sirius Black, to commit a double-murder. Rowling has made it clear that James remained a jerkass right up to his death and it is difficult to understand why Lily married him. But Snape was thoroughly unpleasant to his students (or at least to Harry and his friends) and it is hard to feel any sympathy for him either. Dumbledore could certainly have told him to be nicer at any point within the series; Snape could have moaned about his orders to anyone who would listen, establishing a cover for the moment when Voldemort asked why Snape wasn’t trying to poison Harry in class.

But then, neither Snape nor Lily – nor anyone – were completely good or bad. I had the impression, at least at first, that James had grown up a great deal after the Werewolf Incident, which was nothing more than a cold-blooded attempt, by Sirius Black, to commit a double-murder. Rowling has made it clear that James remained a jerkass right up to his death and it is difficult to understand why Lily married him. But Snape was thoroughly unpleasant to his students (or at least to Harry and his friends) and it is hard to feel any sympathy for him either. Dumbledore could certainly have told him to be nicer at any point within the series; Snape could have moaned about his orders to anyone who would listen, establishing a cover for the moment when Voldemort asked why Snape wasn’t trying to poison Harry in class.

It is easy, though, to see why Snape is a popular character (and was even before he was played by Alan Rickman). Snape is a nerd, like me; it’s easy to see myself reflected in both Snape himself and in how he was treated by a gang of jocks. And it is easy to fall into the trap of hating Lily, even though Snape called her a racist name at a moment when, consciously or not, she must have been waiting for an opportunity to break off the friendship once and for all. Snape has all the nerdy virtues with a bit of wish-fulfilment – he’s pretty much the true hero, combined with being the second or third most powerful wizard in the series – woven in. This hero worship is not altogether healthy, but it is very human.

Dumbledore, by contrast, suffers badly as Harry Potter shifts from a childish series to an adult one. I have already noted, time and time again, that Dumbledore takes a very lax attitude to everything from student safety to winning the damn war. Perhaps he simply has too many jobs – Dumbledore has an impressive series of titles, as we are told right at the start – but it is alarmingly clear that he doesn’t give a damn. He does not even bother to visit the Dursleys, right at the start, and give Petunia the news of her sister’s death in person and, even if one accepts that putting Petunia in a position she could not refuse to take Harry was necessary, one cannot admire it. Dumbledore makes no attempt to train Harry, beyond a few useless glimpses into Voldemort’s past; in hindsight, it is clear that Dumbledore planned for Harry to serve as a human sacrifice right from the start. (This plan has a grisly hole in it – Dumbledore could have killed Harry himself, thus destroying one of Voldemort’s soul pieces well before the second war began.) Dumbledore favours Harry, thus alienating others; he emotionally abuses Snape, treats Sirius Black as a nuisance, hires a string of unsuitable DADA teachers and generally lets matters get out of hand.

Indeed, it is easy to see why so many wizards distrusted him or openly took sides against him. In Book One, Dumbledore seems a dodgy character; by the time we learn about his shocking past, in Book Seven, we are no longer surprised. The only good thing about Dumbledore, at the end, is that he gave his life in a desperate attempt to save Draco from trying and failing (or suceeding) to commit murder. But even that cost him.

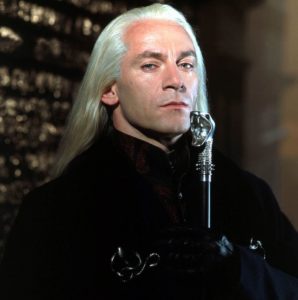

The villains are not, by and large, designed so well. Voldemort loses out badly when it becomes clear that he’s just another abused child growing up into a monster. There’s less subtle about him than I had hoped; he’s little more than a ranting fascist who can’t even be bothered to govern properly – or at all – and eventually walks into a trap baited by his own worst enemy. Lucius Malfoy makes a far more interesting antagonist, but he is overshadowed by Voldemort and winds up a pathetic prisoner in his own mansion; Peter Pettigrew never lives up to his promise; Umbridge, perhaps the most successful of Rowling’s multi-book villains, is a bureaucratic lawful evil monster. I had the impression she was in Hufflepuff, as she’s a clear display of that house’s virtues put to villainous use, but apparently not. But they are all brought down – as are the more unsteady good and basically neutral characters like Lockhart – by their own failings. Voldemort is desperate to live and signs his own death warrant; Malfoy thinks he can ride to power on Voldemort’s coattails and is disastrously disillusioned; cowardly – but not inept – Pettigrew wants to be on the winning side; Umbridge is so desperate for power that she overplays her hand to a staggering degree and loses disastrously. There are lessons here that kids should learn, if you ask me. There are worse ways to learn, too.

The villains are not, by and large, designed so well. Voldemort loses out badly when it becomes clear that he’s just another abused child growing up into a monster. There’s less subtle about him than I had hoped; he’s little more than a ranting fascist who can’t even be bothered to govern properly – or at all – and eventually walks into a trap baited by his own worst enemy. Lucius Malfoy makes a far more interesting antagonist, but he is overshadowed by Voldemort and winds up a pathetic prisoner in his own mansion; Peter Pettigrew never lives up to his promise; Umbridge, perhaps the most successful of Rowling’s multi-book villains, is a bureaucratic lawful evil monster. I had the impression she was in Hufflepuff, as she’s a clear display of that house’s virtues put to villainous use, but apparently not. But they are all brought down – as are the more unsteady good and basically neutral characters like Lockhart – by their own failings. Voldemort is desperate to live and signs his own death warrant; Malfoy thinks he can ride to power on Voldemort’s coattails and is disastrously disillusioned; cowardly – but not inept – Pettigrew wants to be on the winning side; Umbridge is so desperate for power that she overplays her hand to a staggering degree and loses disastrously. There are lessons here that kids should learn, if you ask me. There are worse ways to learn, too.

Rowling also deserves credit for encouraging – and tolerating – the growth of a truly vast amount of fan-fiction. Hundreds of thousands of writers – some with professional dreams, some who wrote merely for fun – took to their computers and wrote Potter fan fiction. And while some of it was terrible, others were professional in quality; indeed, I can name at least two professional authors who got their start by writing Potter fan fiction. Let no one make any mistake. Rowling did a wonderful thing when she chose not to challenge the growth of fiction set in her universes. Authors wrote everything from ‘a day in the limelight’ stories to novel-length tomes featuring a Harry who was more independent – or a Marty Sue – or novels that bashed one or more of the characters. Ron-bashing, in particular, became very popular after the movies came out. Fanon has grown so powerful that canon is often overshadowed: the Dursleys are monsters, Snape deducts hundreds of points on the slightest excuse, Molly/Lily/Ginny are gold-diggers, Draco is a hero, Ron is a villain, Hermione is so smart that she can outthink everyone … it’s fun to look back at canon and see how much has been blown out of all proportion.

And yet, the community shifted as more novels and movies made their appearance. A strange bitterness started to set in, after Dumbledore was revealed as the manipulative bastard to end all manipulative bastards. Dumbledore-bashing fiction became incredibly common, with quite a number of stories no longer able to draw a line between Dumbledore and Voldemort. The early Potter fan fictions saw Dumbledore as a hero – a wise old mentor – and didn’t see the Dursleys as anything more than somewhat neglectful; the later fan fictions saw Dumbledore as, at best, a crazy fanatic and, at worst, an unspeakable monster. And what the alternate versions of the Dursleys did to Harry would have killed a normal boy long before he could be rescued by Snape/Dumbledore/Hermione and her parents/Sirius Black/Voldemort/or someone else. I left the community in 2003 and I was shocked, when I briefly returned, to see how dark things had become.

And yet, the community shifted as more novels and movies made their appearance. A strange bitterness started to set in, after Dumbledore was revealed as the manipulative bastard to end all manipulative bastards. Dumbledore-bashing fiction became incredibly common, with quite a number of stories no longer able to draw a line between Dumbledore and Voldemort. The early Potter fan fictions saw Dumbledore as a hero – a wise old mentor – and didn’t see the Dursleys as anything more than somewhat neglectful; the later fan fictions saw Dumbledore as, at best, a crazy fanatic and, at worst, an unspeakable monster. And what the alternate versions of the Dursleys did to Harry would have killed a normal boy long before he could be rescued by Snape/Dumbledore/Hermione and her parents/Sirius Black/Voldemort/or someone else. I left the community in 2003 and I was shocked, when I briefly returned, to see how dark things had become.

Rowling didn’t do herself any favours, after the series had been completed, by embracing a handful of social-justice warrior talking points. I don’t believe she did the gay community any favours by telling us, a little too late, that Dumbledore was gay. There are a whole string of nasty implications involved, all of which are tied in with the legacy of boarding school sexual abuse scandals in the UK. (The suggestion that Sirius makes about Snape being Lucius’s lapdog in OOTP includes a hint that Snape might have been Lucius’s catamite at Hogwarts, a relationship that would have been thoroughly illegal by UK law.) Nor did she do the black community a good turn when she hinted that Hermione might have been black. I quite agree that we need characters we can identify with, but it’s hard to argue that Hermione is a POC character when she is clearly described and depicted as white. Indeed, Rowling arguably showed more characters of colour than one would reasonably expect from the setting. And I can only roll my eyes at the suggestion that there is anything remotely comparable between Donald Trump and Lord Voldemort. Voldemort couldn’t take over a school; Trump beat the most powerful politicians in America at their own game. Besides, too many people saw Hilary Clinton as a better-dressed Dolores Umbridge. Rowling was on firmer ground when she poked fun at the British Government’s failings in OOTP and HBP.

The core problem with the series, as I have noted above, is that it tried to bridge the gap between childish books and adult books and was unsuccessful. The series grew too grim for children, yet continued to manifest the plot holes and suchlike that grate on adult sensibilities and lead to fan-fiction that puts a more adult gloss on matters. And yet, it draws people in and makes them want to read. Rowling created a wonderful world that introduced countless children to the joys of reading, then encouraged some of them to write fan-fiction or original work of their own. She deserves each and every last bit of her success …

The core problem with the series, as I have noted above, is that it tried to bridge the gap between childish books and adult books and was unsuccessful. The series grew too grim for children, yet continued to manifest the plot holes and suchlike that grate on adult sensibilities and lead to fan-fiction that puts a more adult gloss on matters. And yet, it draws people in and makes them want to read. Rowling created a wonderful world that introduced countless children to the joys of reading, then encouraged some of them to write fan-fiction or original work of their own. She deserves each and every last bit of her success …

… And the world of children and teenage fiction owes her a vast debt.

Leave a comment