Blood at the Root — Review by Christopher G. Nuttall

Review by Christopher G. Nuttall

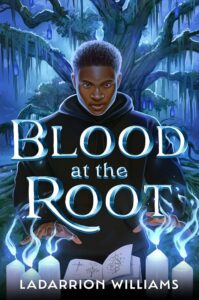

Blood at the Root

-LaDarrion Williams

“Black boys like me do have magic powers. Everything I came to believe this past couple of months, I am finding that to be true every single day. But I will say: that saying of with great power comes great responsibility may be true, but I ain’t ask for none of this. This responsibility was passed down to me. It’s the cards that I’ve been dealt.”

The issue of representation, particularly of characters that are people of colour and/or homosexual, is one that has bedevilled writers and producers over the last few years. The demand for greater representation has led to two separate pitfalls that have undermined the concept of including characters from different backgrounds. On one hand, we have writers and producers who appear to believe that merely including characters of colour is enough and they don’t have to flesh out the characters to make them real people; on the other, we have writers and producers that use their characters as a shield against criticism, implying – sometimes very bluntly – that any criticism stems from bigotry and can therefore be safely discounted. Both issues can make a book or show very hard to watch, let alone review. Fortunately, Blood at the Root avoids both.

By a rather curious coincidence, Blood at the Root is the second African-American themed magic school book to cross my awareness in the last few months. Comparisons between Blood at the Root and the Conjureverse books, as well as Harry Potter, are probably inevitable. Both authors set out to put their own spin on the Harry Potter theme; Williams, for example, openly acknowledged that the core question that led to Blood at the Root was “What if Harry Potter went to an HBCU?” In some ways, the answers put forward by Williams are very different to the Conjureverse books: where one has the conjurers as part of a greater universe, and the story involves interaction between different factions in that universe, the other is far more isolated. A better comparison, in many ways, would be the Black Panther movie. Indeed, the movie is referenced several times (to varying effect).

The plot is centred around Malik Baron, an African-American who has been growing up in an orphanage after his mother mysteriously vanished (and was presumed dead). He had very few friends in the system, mainly a girl called Alexis and a younger boy (Taye) whom Malik effectively adopted as a brother, but lost both when they were fostered out. He also discovered he had magical powers he could neither understand nor control effectively. At seventeen, Malik decided to leave the orphanage, rescue Taye from his foster parents and set course for California in hope of a better life. During their escape, his powers are openly revealed and he is brought to his grandmother’s house. His grandmother arranges for him to go to Caiman University, a HBCU for the young, black, and magical.

The experience is one of ups and downs. Caiman is a very strange place, like all magical schools. Malik discovers that Alexis is another student, and they reconnect; he makes a handful of friends, a handful of enemies, and discovers the teaching staff are – as always – a mixture of friendly and strict, some with agendas of their own that lurk in the shadows, threatening to come into the light. This paradise is threatened by a mysterious sect of African-American magicians who have used forbidden magic, activists (including Alexis) who think the teachers and families are not doing enough to stop the evil wizards, and as Malik is drawn into the gathering storm, he discovers that the official story of his mother’s supposed death may not be entirely true. As tension rises, and it becomes impossible to know who to trust, Malik finds himself caught between the past and the future …

A novel like Blood at the Root largely rides on the main character, and it cannot be denied that Malik is something of a mixed bag. In some ways, I would compare him to Anne Boonchuy. Anne is introduced to us as a deeply flawed character, and Malik is flawed too (although he has far more reason). He is angry at the world, not without cause, and he has a habit of acting without thinking that lands him in hot water more than once and he’s incredibly lucky to survive. In his opening chapters, he steals a car and generally acts more like a criminal than a likeable character or a reliable older brother figure for a younger boy; he does grow up a little, but he is often arrogant, disrespectful, and untrusting. He is also incredibly possessive of Alexis, reacting with intense fury to the suggestion she might be with another boy he dislikes (she isn’t), and it is greatly to her credit that she calls him out for this; later, when the argument calms down, he wonders if he is being a simp.

On the other hand, Malik is genuinely a good person at the root, and he tries hard to take care of both his adopted brother and his family, when he finally meets them. He wants to fight for what he thinks is right, and shows no shortage of bravery in trying to do so. This makes the later series of betrayals all the more heartbreaking, and I suspect it will result in more anger for him in later books. He also shows a great deal of vulnerability at the end of the book, when he thinks he knows who fathered him (although the question is not answered).

The intense focus on Malik, it should be admitted, does leave the other characters feeling more like ciphers than they should. We see everything through his eyes, and while this allows the author a chance to pull the wool over our eyes (in hindsight, one of the betrayals is blatantly obvious), it does make it harder for us to like the other characters or even to get used to them.

The wider world is something of a mixed bag, drawing inspiration from African-American and African traditions, as well as American and British influences. The magical system is not very well defined, I feel, and the political system is difficult to understand; it draws, I feel, a great deal of inspiration from Harry Potter. There are some definite moments of wonder and joy, but also opens questions about why the magical community didn’t intervene more openly in the horrors and tragedies of the Atlantic slave trade, the American Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement. (I have the same question about Black Panther.) It also draws on mythology that is highly controversial, although in this universe it may very well be true.

It also references other major African-American cultural influences, including Black Panther, and sometimes the results are decidedly mixed. At one point, for example, Malik discovers a building named after Chadwick Boseman, and decorated with images from the movie, and gives the Wakanda salute. I do wonder if the author was making a subtle point – the movie deals with betrayals from within, and the flaws in a cracked society, and the same could easily be said of Blood at the Root. A bit later on, Malik openly compares the villain to Killmonger and the villain pours scorn on this idea, although Malik is entirely correct.

The book also slips into discussing the dangers of political activism, in a curiously negative way. The society is under threat, and some of the younger students are no longer prepared to be passive about it … quite reasonable, but they also slip into bad habits and become, in many ways, their own worst enemies. Malik finds himself confronted by students who are prepared to put their activism ahead of everything else, including the safety of the entire school, and it comes across as slightly confusing.

I should mention that there is one major negative point that detracted from the enjoyment of the story. The whole novel is told in first person by Malik, and his voice is so deeply rooted in modern day American slang and African-American Vernacular English that it is sometimes very difficult to follow. I thought one word (hateration) was a formatting error, before I looked it up online and discovered that it was very fitting. Some other words were poor choices: Malik often refers to girls as ‘baddie’ or ‘baddies,’ which again makes a degree of sense but isn’t as accessible as the author might have wished. I honestly feel the author tried too hard to make Malik’s voice sounds authentic, and he is particularly fond of using the n-word, but that might be a result of one of my pet peeves. I often have trouble following books that attempt to reproduce accents and slang, no matter how fitting.

(That said, I should add here that several other reviewers thought the AAVE was overdone or inaccurate and a couple even wondered if the author was not, in fact, African-American. I am not qualified to comment on either of these points.)

In conclusion, what can one say?

Blood at the Root is a story about a young man who is deeply traumatised by his early life, quite understandably, with issues that refuse to go away even when he finally finds himself in a place of (relative) safety. Those issues leave him reluctant to trust others, particularly those who represent the heavy hand of authority, and he winds up learning some harsh lessons about the people who look nice not often being nice, while the ones who are stern and sometimes harsh being the ones who have your best interests in mind. He has his flaws as a character, but those are largely redeemed by his willingness to prove himself a better man than his absent father and become a better brother to Taye, ensuring the younger boy has a far better start in life.

It starts slowly, to be fair, and much of the first third of the book could have done with a second edit. But once the action gets going, it gets going. The twists and turns are surprising – although some are signposted in advance – and it avoids the cliché I half-expected, of a racial war spreading into the magical community. The worldbuilding has its limits – and like Black Panther, there is no excuse for non-intervention – but as a character-based story that is of less importance. Sometimes challenging, sometimes striking, sometimes heartbreaking, sometimes surprising – the author’s decision to clear the decks at the end of the first book is a very brave one indeed – Blood at the Root is well worth a read.

See Blood at the Root on Amazon.

Leave a comment